We organize funerals for our dead. What should we do for a dead body of water? In November, 1969, the nascent environmental organization, Pollution Probe, decided that for all intents and purposes the befouled, if not outright poisoned Don River, which flowed through Toronto to Lake Ontario, was dead. The only thing left: organize a funeral. Peter Love, a second-year student at the University of Toronto at the time, remembers his “52 Woody Station Wagon was used as the hearse for the Burial of the Don, an event covered by all the TV networks and newspapers.” Flash forward to November, 2019, and Pollution Probe is no longer nascent, rather it is golden, with former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney filling the role as keynote speaker for Pollution Probe’s 50th Anniversary Gala. 1969 to 2019: Golden Anniversary for a truly original Canadian environmental organization that was founded by university students two years before the more internationally well-known (and Canadian-founded) Greenpeace.

Environmental movements and environmentalists are now everyday characterizations but half a century ago they were emergent. While climate change — the slow warming of the planet unseen until the effects burst into Australian flames — has emerged as an existential crisis, in the 1960s it was visible-to-the-naked-eye degradation of the planet that drove many into action. Untreated industrial effluent and raw sewage pumped into waterways; smokestacks spewing black plumes high into the sky; perceptible smog, like a dome, covering major cities in the leaded-gasoline days before catalytic converters; common litter strewn along the sidewalks and roadways everywhere you looked.

But something else, too, in those days: the media actually mattered. Public media institutions, like the CBC, made a difference, their reportage garnered interest and changed perceptions — which is where the story of Pollution Probe begins.

Peter Love joined Pollution Probe in its early days in 1969 and his early involvement led to his becoming one of Ontario’s leading environmentalists, especially in regards to energy and energy efficiency. When the Ontario Power Authority was created in 2004 Peter was appointed Chief Energy Conservation Officer. I’ve known Peter, through my old corporate days at Union Gas, for over twenty years and when I interviewed him for the Profile he told me “Probe was created in 1969 after a series of articles by Sherry Brydson who was a writer for the U of T student newspaper called The Varsity. These articles were based on the CBC documentary called The Air of Death by Larry Gosnell. This documentary was shown at U of T and at the end of the meeting, a small group (including Sherry and Tony Barrett) decided to form Pollution Probe”.

The Air of Death was a compelling TV documentary, not only for the impact on the public, but also for the government pushback it engendered. The documentary exposed serious air pollution and informed Canadians the issue was not confined to large American cities like Los Angeles. Sulphur dioxide, benzopyrene, carbon monoxide all gathered in the air Canadians were breathing as well. Because the documentary was not shy about identifying responsible industries, an enormous backlash ensued with the Ontario government launching an inquiry to discredit the CBC documentary.

The inquiry had at least two ramifications. One, it cast a pall, at least temporarily, over the type of hard-hitting journalism that Air of Death exemplified. As MacLean’s magazine’s Douglas Marshall wrote in his May 1, 1969 TV column: “What has happened to Air of Death, the CBC’s controversial program on air pollution, since it was broadcast for the first and last time on Oct. 22, 1967, shouldn’t happen to a sleazy 8-mm underground movie. It’s a pity the people of Canada haven’t had a chance to see a repeat performance. Air of Death was, beyond question, one of the most powerful and relevant documents presented on Canadian television in recent years. Yet this dramatic example of TV’s potential has been subjected to two costly investigations, and the crucial issues raised by the program have largely been obscured by the clamorous debate over how they were put across.”

The second ramification? The birth of Pollution Probe. As the organization says about itself on its website today: “Since 1969, we have been defining environmental problems through research, promoting understanding through education and pressing for practical solutions through advocacy.”

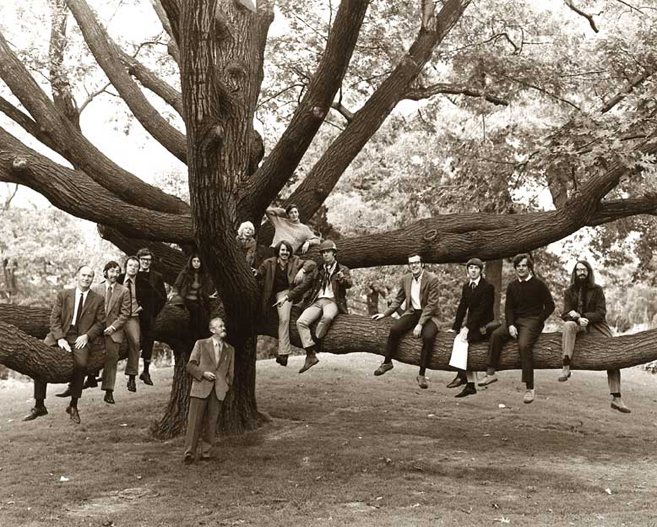

The formation of Pollution Probe in 1969 came from a fascinating intersection of hippie ’60s radicalism, university intellectual scholarship, and business-connected affluent students who’d graduated from elite private schools like Upper Canada College. Tony Barrett, one of the UCC graduates, had the sense of humour we associate with Yippies (otherwise referred to as Groucho Marxists) of the time — he was well-known for wearing a plastic toy helmet to go into battle to clean up the environment — yet was comfortable in the halls of major media, corporations and government.

In 2010, Ryan O’Connor wrote his PhD Thesis on those times, and the founding of Pollution Probe, “Toronto the Green: Pollution Probe and the Rise of the Canadian Environmental Movement” (he subsequently turned it into a book The First Green Wave.) Ryan opened his thesis with this story:

“One day in September 1969 Tony Barrett and Rob Mills found themselves in the lobby of the Toronto Telegram. Friends from their days at the prestigious Upper Canada College, the duo were now waiting patiently to meet the newspaper’s owner-publisher, John Bassett, with an unusual proposal on behalf of Pollution Probe, the upstart environmental non-governmental organization [ENGO]. Pollution Probe had recently acquired the pro bono services of Vickers and Benson, Canada’s leading advertising agency. However, lacking the funds to purchase space in any of the city’s leading newspapers, Barrett and Mills had come to propose that The Telegram donate space for their full-page advertisements. Having failed to make it past the reception area at the Globe and Mail and Toronto Star, the duo was surprised to be ushered into Bassett’s office and given the opportunity to make their pitch. Mills, who was barely out of his teenage years at the time, can still remember the scene. ‘He [Bassett] was a scary guy. Very tall, very severe, very gruff …. He says, “Why the hell should I bother doing this?” After delivering a three-minute pitch on the societal benefits of their proposal, Mills remembers that ‘we just about melted when he said, “Well, I’ll give you eighteen pages on the back page.”’

EIGHTEEN PAGES ON THE BACK PAGE OF A TORONTO DAILY NEWSPAPER! Imagine that.

My friend Ken Ogilvie, who was the Executive Director of Pollution Probe from 1995 to 2007, shared a story with me that Tony Barrett had told him during the only time they met in person, a lunch. As Ken remembers it, “Tony’s family knew Bill Davis, Premier of the Province of Ontario. He knew that Premier Davis liked the butter tarts that were made or sold at the University of Toronto, which was located across the street from the Ontario legislative buildings. So, one day, this eccentric Pollution Prober decided to pick up some tarts and pay a visit to the Premier. He took the tarts into the legislative building and went to the Premier’s office. He walked up to a woman in the outer office area and said he wanted to see the Premier. She asked him if he had an appointment, and he said no, but that he’d brought some butter tarts for Mr. Davis. The woman seemed a bit startled, then she said the Premier was in a meeting in his office. Tony said that was fine. He would wait outside until Mr. Davis was done. The woman reluctantly dialled through to the Premier and said a Mr. Barrett was outside waiting to see him, but he had no appointment. To her evident surprise, the Premier told her that he would see Mr. Barrett when his meeting ended. Which happened! Tony entered the Premier’s office and told him he’d brought him some butter tarts. The Premier invited him to sit down, and they munched away and had a great chat. It worked so well, according to Tony, that he periodically repeated the feat. He and Premier Davis ate tarts, and chatted, but sometimes they didn’t even speak. They just ate the tarts and Tony left the office.”

Beyond government, Pollution Probe engaged corporations from the beginning, and still does, because in the end the corporations need to be part of the solution not part of the problem. The relationship can be characterized as “tricky” or “tense” but informed research requires peer review and industry has experts within their employ. Corporations also have funding. When I interviewed Ron Nielsen, who had worked with Ken for many years after meeting at the Ontario Round Table on Environment and the Economy, first as a consultant and then as a staff member at Pollution Probe, he told me that “Ken recognized the value of a balanced funding approach and always championed the 1/3- 1/3 – 1/3 of public donations, government funding and corporate funding.”

Engaging industry is not without its critics as anyone who has read Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate and On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal know. But Pollution Probe thinks it is possible to navigate independence, stay true to honest, science-based research, and engage industry. Bob Oliver followed Ken as Executive Director in 2007 and when I caught up to him to reflect back on the essential aspect of Probe he said, “From my perspective, Pollution Probe addresses environmental policy in a way that most people would consider ideal. That is, in an informed, objective and practical manner. Pollution Probe, in my opinion, has been able to withstand the lure of expedient politics (i.e., partisanship) in order to achieve progress on policy. That has made many of the policies on which Pollution Probe was a key advocate durable … capable of surviving political turnover. I think that Canada needs such an environmental organization.”

The tension is real when you try to balance the funding needs and the fundamental requirement of honest, scientific research, particularly in a time when partisanship seems higher than ever. Ron Nielsen spoke to the tension very clearly when he told me “it’s so much more difficult to find funding, there is much less willingness to support NGO efforts for the broader good — both government and industry are so much more driven by self-interest now, that they fully expect the NGO to sellout to their interests. In this setting, it’s very challenging to find the funding that allows an organization to retain its independence and authenticity, and not have to sellout to the funder.”

I have no doubt about the challenge as articulated by Ron. Yet meeting that challenge is critical. The history of Pollution Probe in their combination of research, education and engagement with all segments of society — the public, government, business, and media — needs to be extended long into the future. If you read my last Profile, on Ken, you will know that many folks connected to Probe in some way, shape or form gather at the behest of Ken for a pub evening called Wings Night. One of Wings Night’s regulars is former journalist Michael Keating, who was an early Environmental Reporter for the Globe and Mail in the 1970s and 80s. He recounted for me in a recent email exchange about the amount of information he relied on from Probe during his career and summed up by writing, “during the early 1980s, Pollution Probe lived up to its name with a focus on water pollution, particularly in the lower Great Lakes. For me as a journalist, as well as others in the news media at the time, Probe was a major and trusted source of information and opinion. The organization had a good network of contacts with credible scientific researchers. It often took existing government environment reports and made them more visible by contacting the news media. While the group made its name by going after polluters and governments it saw as too soft on industry, it was also playing a positive role with news media and using the reports to push for pollution cuts and to protect health.”

I think it’s interesting that his summation ends with “the group made its name by going after polluters and governments it saw as too soft on industry”. When Pollution Probe engages government and industry for funding, it is called into question regarding independence; yet at the same time journalists have always looked at it for its very independence, its integrity. The current Executive Director, Chris Hilkene, understands this balancing act (my next Profile is of Chris and I’ll examine this in more detail) and no doubt received criticism in some corners by securing former Progressive Conservative Prime Minister, Brian Mulroney, as the guest speaker for Probe’s 50th Gala. But don’t forget that Mulroney pushed President Reagan hard on the acid rain issue in the ’80s and the eventual emissions trading program proved successful and became a model for those pressing for carbon emissions trading as one of the tools to combat climate change.

The virtual tug-of-war Pollution Probe must engage in to keep its independence and raise money to keep the lights on, and staff employed, has been going on from the early days right on through. As I wrote in the last Profile, Ken stepped in to save Probe in the 1990s when it teetered on the brink of insolvency. Bob Oliver told me that a little more than a year into his tenure as Executive Director when he succeeded Ken, “the government funding landscape changed radically. In the context of the 2008 financial crisis, the federal government cancelled existing contracts and put a moratorium on any new project funding. This hurt Probe and many other public interest groups, too. Shortly thereafter, the Ontario health care scandal led to discretionary funding freezes throughout the Government of Ontario, which was our second-most significant funding source. This drove the organization deeply into debt. I had to slash overhead, let good people go, and reorient the value proposition of Pollution Probe toward the private sector – the only other ready source of revenue available to us.”

So, throughout their fifty years, Pollution Probe has struggled — but the key is they have survived for fifty years! The relentless march of climate change and the failure of world leaders to coordinate significant, immediate policy changes has led many to hand-wringing, pessimism, and, for some, utter despair. Yet Pollution Probe continues to fight. Why? Well, as I wrap up this Profile, let me share a story I first heard at Pollution Probe’s 35th Gala and asked Ken to re-tell it as he knows the story far better than I:

“In the 1970s, Pollution Probe took on the cause of getting phosphates out of laundry detergents, which set the organization at odds with detergent manufacturers such as Procter and Gamble, and Colgate. As the story goes, after a huge battle, the government of Canada regulated the amount of phosphates allowed in detergents, and during the next decade or two Lake Erie recovered (although not completely). Several years after the regulation went into effect (and, I note, the companies found an acceptable substitute for most phosphate uses) the CEO of Colgate called two staff to his office, and Monte Hummel and Peter Middleton went there. They were expecting to be yelled at again, but a surprise awaited them. They sat across the CEO’s desk and he pushed an envelope over to them. It was a personal cheque for $5,000 — a tidy sum in those days. He said Pollution Probe had done the right thing, and he had done ‘his job’ in fighting the regulation. He asked Monte and Peter to keep his donation quiet for a few more years, presumably until he was no longer at Colgate.” In a subsequent email to verify this story with one of the principals involved, Monte Hummel, Monte wrote, “In fact, in the early days, there was an influential circle of prominent Canadian businessmen who acknowledged privately that they needed a ‘good kick in the seat of the pants,’ and consequently said so to their peers, and/or supported us financially, and/or provided us with access to make our best case—in their board rooms, in the most hallowed private clubs of Toronto, and even with guests in their Rosedale/Forest Hill homes.”

Perhaps Pollution Probe should add that to its stated mandate: giving businesses and business people a good kick in the pants. If you want to learn more or get involved visit Pollution Probe’s website.

Next up, a Profile of the current Executive Director, Christopher Hilkene. Read not only about his work at Pollution Probe but also the music recording contract he walked away from and the ridiculously romantic first date with the woman he would marry — a tale seemingly ripped from a box-office-busting romcom.

I hope you come back.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply to Gerard Coffey Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Dear Ed, I’ve read this before and had some reservations about the piece. This time I’ve decided to comment. It’s a ‘nice’ almost eulogistic text, which fails to mention so much of the history of the organization, about Don Chant as a major mover in the early years about the foñlks responsible for setting up Ecology House, and all of us involved during the ‘intervening’ years (1980 -1990) which were crucial in the definition of Probe as a mild mannered rather than radical force for environmental change. Too bad.