In July 1997 I went back to Newfoundland for the first time since I was a child. In 1968, after the factory in London where he worked closed, my father decided to move back to St. John’s which, of course, included my mother, sister and me. I’d visited St. John’s once, 1966, in a grand Newfoundland celebration known as “Come Home Year”. For the brief time we lived in St. John’s in 1968 we stayed in our 15 foot trailer parked in the driveway of the only St. John’s home my father lived in, the house he was born in and his half-brother Bill Davis owned: 35 Goodview Street. Up the street at 43 Goodview lived my dad’s first cousin, Mary, who he’d grown up with. Her last name, through marriage, was Sharpe; she had five children.

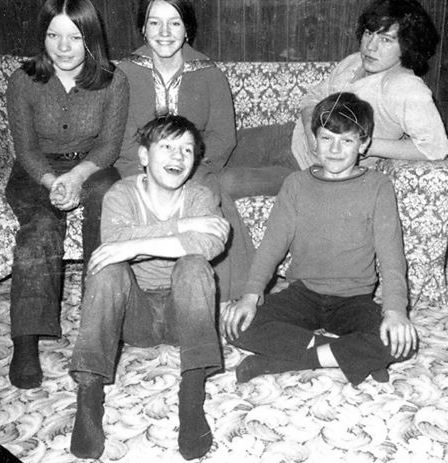

I can’t say that I remember any of my five Sharpe cousins — Bill, Marie, Joan, Doug, Bob —from that summer but when I returned as an adult (my father long dead, succumbing to his second heart attack in 1977, just weeks after his last trip to St. John’s), an immediate connection bonded me to them. The time I spent with them was not only delightful but also meaningful; it provided insight as to my father’s desperate need to move back that time — though his plans probably foolish — an understanding that had always eluded me.

The sense of place, of belonging, in Newfoundland is both deep and ironic. I say ironic because the land, the climate, can be inhospitable. Perhaps there exists an inverse relationship in Newfoundland — the conditions so harsh that fellowship amongst people is so critical. What I began to meditate on, as I got to know these Sharpe cousins, was that they’d all stayed in St. John’s, worked, married, thrived. Despite the constant out-migration of Newfoundlanders, before and after Confederation, these five remained. The more I got to know them, the more I talked over the years regarding both our shared history and their own personal history, the more I appreciated the reality of Newfoundland through their eyes, especially St. John’s. I decided to create a series of Profiles of this family, writing about them collectively and individually, because I think their stories, connected, can provide insight, at one and the same time, into the diversity and the singularity that is Newfoundland.

Newfoundland is rich in culture and history, yet for most outsiders it is too often reduced to either cute, tourist-inducing images or snickering Newfie jokes. (You should know that to an increasing number of Newfoundlanders, Newfie is very much construed as a version of the N word.) The isolation of this great rock in the North Atlantic is emphasized yet few understand the significance of the vast array of influences — British, of course, but also the American military bases during the Second World War and immediately post-war, as well as the continuous European fishing vessels sailing in and out of St. John’s harbour. Music is not simply their own unique brand of folk music; Newfoundlanders of the last hundred years have grown up as much as anyone else in Canada with popular music, and film, and television. The ever-shrinking world, continually connected, includes that rock-in-the-Atlantic as much as any place on the planet.

You can source a wide range of Newfoundland authored books to understand aspects of the island, non-fiction history like Cassie Brown’s tragic account, Death on the Ice, or novels dealing with historical events like Lisa Moore’s February and Wayne Johnston’s The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, or you can go to the silly, such as comedian Mark Critch’s Son of a Critch – A Childish Newfoundland Memoir. You know what, let’s start with the silly and quote from Critch’s childish memoir:

“The real Newfoundland is not like the award-winning tourism ads. I’ve lived here all my life and I’ve never stood on a cliff with the sun splitting the rocks as two whales breach in a choreographed ballet while some little red-headed girl plays the fiddle for me. I have, however, stood in a five-foot snow drift in the month of May while two nimrods drive by in a beat-up Camaro, Great Big Sea blaring out the window, throwing Tim Hortons cups at me and giving me the finger. But they don’t make hooked rugs with that on them.”

Of course, you can see whales breach (I have) and Newfoundland’s folk music is beautiful. Then again, I have witnessed those beat-up Camaros bombing along Topsail Road, though in 25C weather in July. My cousins Bill and Doug have been musicians since they were teenagers, drummers, whose early influences are from the 1960’s British Invasion and American Rock ’n Roll, not Newfoundland legends Dick Nolan and Harry Hibbs. The life tapestry of Newfoundland up to and including the current reality is complex, layered, like its history, like that family of Sharpes. I’ll begin with some family history so I can guide you through those many connected lives, from then to now.

My paternal grandfather, Andrew Seward (the spelling of our surname had the a added to Seaward along the way), and his brother Michael — the Sharpe’s maternal grandfather — were born in the early 1880’s in a small Newfoundland fishing village on the west side of Trinity Bay called Gooseberry Cove. Not surprisingly, they found employment at sea as fishermen, sealers, merchant marines. In 1916 they served together on the Newfoundland ship S.S. Stephano. By then the Stephano was part of North Atlantic lore, of tragedy, of what is known as the “1914 Newfoundland Sealing Disaster” that Cassie Brown wrote about, and Wayne Johnston fictionalized. Nearly eighty men died, sealers on the ice floes in a screw-up of epic proportions involving the captain of the Stephano, Abraham Kean, and the captain of the S S Newfoundland, Kean’s son Wes. By 1916 that disaster was in the past, the commission of enquiry done, and the Stephano had been re-fitted as a passenger and cargo vessel; the destruction of the ship, however, was very much in the immediate future. On October 3, with World War One raging, a German U-Boat sank the Stephano not far off-shore from Martha’s Vineyard but clearly in international waters. The Americans were not at war at the time, maintaining a policy of neutrality until April, 1917. The Seward brothers survived: no lives were lost when the ship went down, the Germans signalling their intentions and allowing the Stephano’s captain and crew to disembark before torpedoing the vessel.

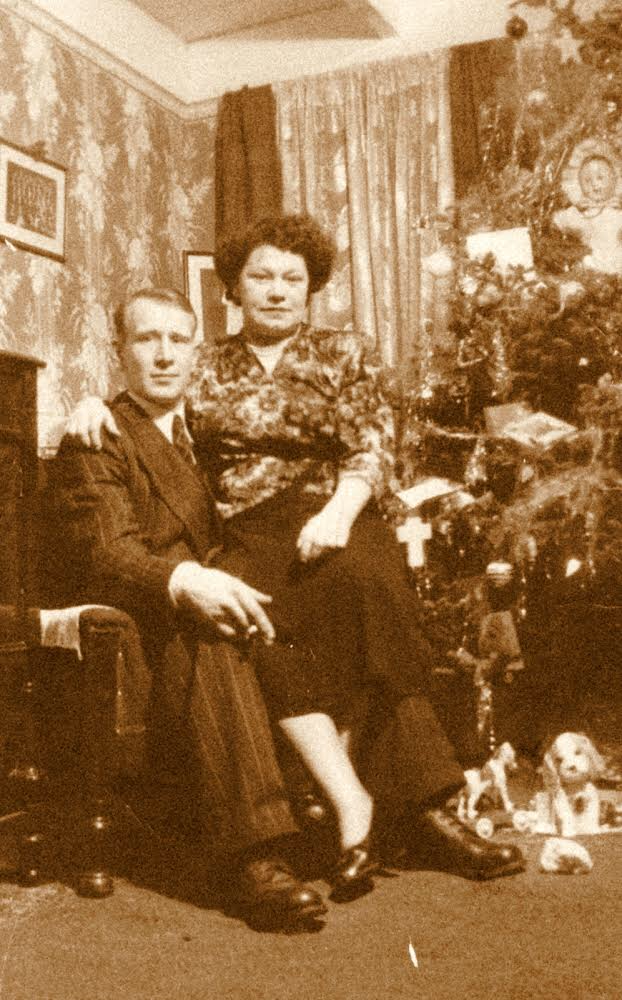

In December, 1929, Andrew and Michael Seward each received $600 disbursements from reparation funds paid to the Newfoundland Government by Germany, part of the settlement reached in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. By this time the brothers were firmly settled in east St. John’s, living two doors apart on Goodview Street. My father, Ed, would have been eight months old when the cheque arrived, the youngest of a large, combined family. Andrew had a daughter when his first wife died and later married a widow, Mary Jane Davis, who had two daughters and a son. Together, Andrew and Mary had three boys. Two doors up the street, Michael and his wife Martha had eight children although three died very young, between the ages of thirteen and twenty-seven months. In the decades to come, as they became adults, many of Andrew and Michael’s children left Newfoundland, moving to Ontario: either London or Toronto. My Uncle Mike (you should know there are a number of Mike Seawards in the family, including my son) arrived in London in 1947, my father following him two years later. Eventually a number of Michael’s sons joined them — Frank, Leo, Bill. But Mary Seaward, the oldest and the only daughter to survive childhood never left Newfoundland, never left St. John’s, never left Goodview Street. She married Ambrose Sharpe and together they had five children, my Sharpe cousins. All five born and raised on Goodview Street and while none of them now live on the street they have, as I said, remained in Newfoundland.

The marriage of Mary Seaward to Ambrose Sharpe started with great controversy, she Catholic and he Protestant: to Newfoundlanders in the middle of the twentieth century it constituted a “mixed marriage”. As Joan, our family historian, puts it: “Dad was Protestant, born on July 12, 1920, the anniversary of the “Battle of the Boyne” when King Billy beat the shit out of the Catholics — Orangeman’s Day. When he grew up he pissed off my grandmother Sharpe when he married a Catholic.” The house they settled into, 43 Goodview Street, had been in Mary’s family since 1890. Mary’s mother, Martha, was two years old when the Great Fire of 1892 raged through St. John’s, coming close enough that it singed the backside of houses on the east side of Goodview Street. For all five of my Sharpe cousins, however, that house represented stability, encouragement, musicality, an open place to all, sanctuary for any of their friends. On top of that, education reigned supreme.

Economic difficulties are the one factual aspect of Newfoundland that most people understand. Bob stated it to me this way: “It takes a lot of will to live here. The climate fights you everyday. Its a huge land mass split by an ocean straight that’s bound by ice for months at a time. The economics of servicing a large area with a small population base is staggering at times. The payoff at the end of the day is a great sense of peace, contentment and accomplishment.”

Steady employment is not always easy but it is key. Critical to achieving steady employment is education, not only to provide you with specific, employable skills but to provide you with the ability to think critically, to understand and assess possibilities. Neither Ambrose nor Mary went beyond grade eight but they valued education. For Mary, a bright student, the sudden death of her father Michael Seward during the Great Depression meant she was pulled from school to go to work and help the family survive. As it was, her three youngest brothers were sent to the orphanage, Mount Cashel. Mary became the maternal figure in the family, eventually bringing her brothers back home to 43 Goodview Street.

Ambrose left school after grade eight to work on a family farm but, as Joan remembers hearing from her father, “he signed up for World War II because he didn’t want to dig spuds.” When he returned from the war he and Mary met, married, lived at her Goodview Street house and he secured work in the boiler room at the General Hospital. When I interviewed each of my cousins separately for this Profile, they all told me the same thing: their parents stressed nothing more to them than the importance of education. And they all have the same memory of doing their homework at the kitchen table, in the evening, alongside their father who was also doing “his homework”. Though he may have struggled with math he understood the importance it held in the many correspondence courses he enrolled in to progress up the ladder as a stationary engineer at the hospital. “Getting a ticket”, he would stress — the “ticket” meaning certificates required in employment.

The encouragement and example Ambrose and Mary set for their five children worked: all five “got their tickets”; they completed post-secondary education to help them secure employment and find their passions. Over this next series of Profiles you will read about these five sterling people — Bill, Marie, Joan, Doug and Bob — and how they have thrived as educators, as musicians, as union leaders, as successful men and women who did not leave Newfoundland to flourish. You will read about their connections to the city of St. John’s and much everything else, from Rock ’n’ Roll to the hit CBC TV show The Republic of Doyle. Hopefully, you will, through their stories, understand not just their personal history, but understand a bit more of the history of Newfoundland and its culture. A place with 500,000 citizens that, in 2019, had two writers shortlisted for Canada’s most prestigious literary award, the Giller Prize. Think about that: Canada’s population approaches 40 million but a province with less than 2% of the total scored 33% of the novels nominated to the short list.

The first Profile will focus on the oldest of the five, Bill, teacher, entrepreneur, musician. Learn a little about his popular band, Billy and the Bruisers, and his long-running radio show, Cool Jazz, while you read about his view of Newfoundland’s place in our country and in this world.

I hope you come back.

8 Comments

Leave a Reply to Sheila Pendergast Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

This is great Ed, I cant wait for the next issue about our cousins

Couldn’t stop reading once I started!! Eager for the next segment, soon I hope.

(Ed, I didn’t know of your roots in Newfoundland. 4 of our best friends were born & raised there but never shared their history as vividly as you’ve been able to recount.)

Thanks Ed

You captured me I’ll be sure to tune in ❤️

Beautiful work Ed can’t wait to come back and read some more. So hurry up and start writing..❤

Hey Ed, I thoroughly enjoyed the intro and am looking forward to more. I will pass this on to a friend who I know will be as interested As I am. Thanks so much for including me on your list.

Ed, these profiles are great! I lived next door to the Sharpe family, at #45. Unfortunately, we moved to Kitchener Ave when I was around 12 years old or younger. But to this day, i still consider the Sharpes my friends! What a wonderful, loving, giving family. I’m looking forward to reading more of your profiles.

Thanks John, I hope you enjoy the rest of the Profiles when they are published — the plan is every two weeks.

Ok, just now reading the introduction, however I’ve read all the profiles. Ed is an irrestible story teller. In describing these five, he hasn’t written a dull word. They could be your neighbours on any street in any town, anywhere. However, they just happen to be my cousins, on my fathers side, S and boys oh boys am I ever proud. S.