Late at night, early April 1968, found 26 year old Brian Bland driving through town to his parents’ house, a short journey but one requiring him to stop at checkpoints guarded by uniformed young men. The soldiers reminded Brian of how he looked only a few months earlier, before he returned from his tour of duty in Vietnam. He was to be in a war zone no longer, yet here he was among soldiers, their weapons, their armoured vehicles, and the streets lined with wreckage throughout his hometown: Memphis, Tennessee. These were the days following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King — a murder that took place less than twenty-four hours after Dr. King delivered his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech.

As a university graduate of broadcast journalism, Brian served in Vietnam as a Division Photo Officer, a captain. When the onslaught of reporters descended on Memphis in the wake of Dr. King’s assassination, the local police department had no ability to deal with the press in such great numbers and sought help from the community relations chief at Memphis State University who, in turn, reached out to a young man he knew was temporarily in town. Brian Bland found himself in the maelstrom, not beginning his life-long career as a broadcast journalist but as part of the police liaison team, dealing with the aftermath of a great stain on his beloved city.

I know all of this because in the winter of 2018, when I joined the Write Away group in Santa Monica, I closed my eyes, tilted back my head, and listened to Brian read his essay: “My 1968”. To my ear, Brian has the voice radio demands: deep, confident, melodic, compelling. I remember that first year, listening to him read his work Tuesday after Tuesday, wondering if he was as great a writer as he sounded — I mean, for me that voice could make reading the phone book sound interesting. But Brian has shared some of his writing with me over these last few years and it reads as beautiful as it sounds.

Born in Memphis just months before the US entered World War II in 1941, Brian remembers being at home from ages 3 – 6 wearing a replica of his father’s navy uniform. He calls both his parents “liberal-leaning patriots” and says his father was “fortunate to have been able to get into Naval administration” given he had a wife and young son at home, and was stationed in Cleveland, not overseas. His parents were originally from Illinois and Brian returned to their home state to attend the University of Illinois “due to its excellent journalism school that had a very up-to-date broadcast department. The school ran its own radio and TV station and had a student radio station, to boot. In senior year and in grad school, we did a lot of actual reporting. The campus sprawled across the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana, each with its own form of government; we reported on both, did on-air editorial summaries of the state newspapers, did regular radio and TV newscasts, shot film, and carried suitcase-size audio tape recorders.”

During his time at graduate school, Brian found a job at the newly minted FM station in Champaign-Urbana. Another one of the essays I heard Brian read in the winter of 2018 was of that experience entitled “WLRW, 1963 — In Stereo From The Cornfield”. He was polishing the essay to submit to a proposed anthology about the “old days” of radio. In Brian’s case, a humorous remembrance of working for local real estate developer Frank Stewart in a basement radio station — literally. The developer built three homes on land extracted from a cornfield of which one, “in addition to serving as a walk-through model for prospective homeowners, also housed Stewart’s pet project — his own radio station, a lifelong dream that was reflected in its call letters: WLRW, for Wonderful Little Red Wagon”. The anthology did get published last year and Air is available through Books By Hippocampus (follow this link). I read the collection and found all 25 essays to be enjoyable, funny, informative reads even if the other 24 were not quite as well written as Brian’s.

While at university, Brian was enrolled in Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC). As Brian explained: “ROTC was an offshoot of an 1862 act of Congress that gave land to states to build colleges on. The states had to agree to have a military training program at their land-grant universities. The idea was to build a nationwide corps of young men who’d been trained to be military officers, even if they didn’t make a career of the military…. At the time I went to the University of Illinois, starting in autumn of 1959, ROTC was a required course for freshman and sophomore males.”

The other aspect of the US military tradition to understand is that conscription, which we commonly call the draft, had been a legal reality in America since 1940 and did not disappear at the end of World War II, but continued until 1973. I think many often view the draft as a Vietnam era phenomenon because the number of young men drafted swelled so dramatically during the sixties. Under General Westmoreland’s insistence, the US military presence in Vietnam increased from 16,000 in 1963 to over 500,000 by 1968.

With a graduate degree in broadcast journalism along with his ROTC training, Brian entered the Army on active duty in late 1964 joining the Signal Corps as a 2nd Lieutenant. After 21 months with a film/TV unit, where he made combat training films and had been promoted to 1st Lieutenant, he decided to extend his duty obligation. Brian volunteered to go to Vietnam as a photo officer for the 25th Infantry Division, and six months later he landed in Vietnam to oversee a detachment of combat photographers who produced mostly still photos that documented that division’s part in the war, as well as some intelligence gathering. While there he was promoted to Captain.

I don’t know about you, my reader, but when Brian communicated all of the above to me I had one simple question: why volunteer to go to Vietnam at all? I mean, Brian could have served out his service Stateside, making training films.

He replied: “My motivation to go to Vietnam was complex. On the most basic level, I felt that with four years of ROTC and 21 months of active duty, I was well-trained to do certain specific jobs in Vietnam. Someone would have to do those jobs (emphasis mine). It seemed like the wrong time to be leaving the service. Most of us drew a parallel between Korea and Vietnam, and thought of Communism as a bloc — USSR, China, North Korea, North Vietnam — which had a common interest in weakening the U.S. and increasing its world influence.

“On a personal level, my marriage had ended (in part due to my thinking about going overseas and perhaps making the military a career), and I had no kids. Although there was some opposition to our involvement in Vietnam, key events such as the Tet offensive in January 1968 and the revelation (in ’69) of the Mỹ Lai massacre in 1968 were in the future. JFK himself (killed when I was in grad school) had not only served in WW II, but stared down the USSR in Berlin, and over the Soviet missiles in Cuba.”

A key to my friendship with Brian over these last few years has been to come to know an honest man who has changed as he has matured, learned, been open to understanding realities as new facts come about. In my adult lifetime, America has become more and more problematic as one of the world’s great democracies, starting with Daniel Ellsberg’s revelation of the Pentagon Papers, Ronald Reagan’s Iran-Contra deal, Bush-Cheney’s war in Iraq, the ongoing issues of race and, of course, the current scourge of Donald J Trump. Yet the friendships I have made in California these last few years are reflected in Brian Bland, thoughtfulness, compassion, a world-view extending beyond American borders. Brian, who began his professional broadcast career later in 1968, after the Dr. King murder, has been a keen observer as a journalist and I always hear a well-informed critic in the essays he writes.

Soon after Dr. King’s killing, Brian left Memphis to begin his broadcast journalism career in San Francisco where he’d fallen in love with a young woman he’d met in 1966, before going overseas. From June to October his job search came up empty as he discovered that “seemingly everyone in the country wanted to move there, and everyone who had a radio or TV news job there planned to stay put forever…. Finally, I began presenting myself as a news writer, which led to my first paid news job, in mid-October, at an independent TV station in Oakland, across the bridge from San Francisco.”

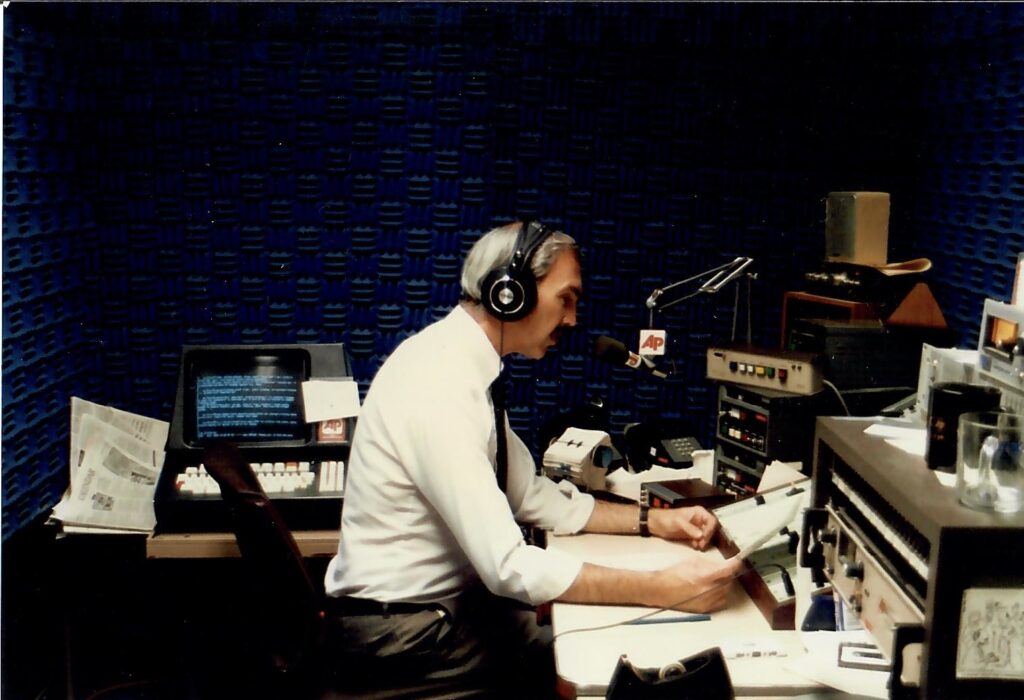

The romance did not work out but the career certainly did. For ten years, from ’68 to ’78, Brian worked his way up the career ladder from being a news writer and vacation-relief news producer at an Oakland TV station to a news director and anchor at cable TV stations in Sunnyvale and Santa Clara (just a bit south of San Francisco/Oakland), then to Nevada at a Reno TV station, until finally settling into AP Radio in Los Angeles. Initially hired as a writer/reporter which included assignments for the AP Radio network, Brian became the network’s L.A. based correspondent in 1982, a position he held until retiring in 2006.

Despite the title of “Western Regional Correspondent” for AP Radio, Brian actually wound up covering major stories in 26 states stretching across the U.S. These assignments ranged from the interesting — Shuttle landings at Edwards Air Force Base, though I suspect by the 20th they became somewhat routine — to the necessary — 7 national political conventions — to the horrific —mass shootings, including the 1984 massacre at a McDonald’s in San Diego where 21 people were killed and 19 others wounded. Along the way he also managed to climb aboard Air Force One a couple of times, when AP’s Radio White House Correspondent had some time off and the President was making a swing through the west. One of Brian’s favourite memories is discovering Air Force One stationery on the plane and writing a cute letter to the young son of a good friend. The boy was fascinated with airplanes and Brian’s letter explained that he was actually writing onboard one of the most famous airplanes in the world. At the end of the flight, one of the stewards took the letter, sealed it in an official Air Force One envelope, and dropped it in the mail. That’s taking advantage of a job perk in the perfect way: delighting the young child of a good friend.

Other assignments included covering various disasters such as earthquakes and major fires. One such job found Brian at a fire near Sonora, California in late August 1987. Days later, on a Saturday, the fire calmed down. A good friend’s 50th birthday celebration was being held 135 miles away, so Brian told the assignment desk in D.C. “that I was going to ‘run down the hill to San Francisco’ but be back in the morning.” Smoky and dirty, he arrived just as the other guests were showing up at the party. After a quick shower and change of clothes (luckily his friend was Brian’s size), he was introduced to a woman named Jeanne. They hit it off immediately, enjoyed the party together until he walked her to her car at 1 a.m., and spent the next fourteen months dashing back and forth between their respective homes in L.A. and San Fran. Finally, and as Brian put it to me, “bravely, Jeanne with her eight-year-old son, Ryan, moved to my Santa Monica apartment and, as a new nurse, promptly got a job. About twenty months later we were married at the Inn of the Seventh Ray, up Topanga Canyon, with a bevy of friends, mostly from out of town, including both of our mothers. One of my boyhood friends, an Irish-Jewish Franciscan priest, performed the secular outdoor ceremony. We just had our 30th anniversary on Bastille Day, July 14. Ryan, 39, is married, has an 8-yr old son and 13-yr-old stepdaughter — so, I’m a (step) grandfather.”

Less than three weeks after the wedding, Iraq invaded Kuwait, and a few months later Brian headed back to a war zone as a journalist rather than a soldier. When Brian and I chatted about this time in his life I asked him how it felt and he used the word “eerie”. Before going to Saudi Arabia, and then Kuwait, he was assigned to cover the Pentagon briefings in Washington, D.C. After three weeks, one of his producers told him he had a couple of days to put his affairs in order. The source of the “eerie” feeling: Brian had gone to Vietnam a young man, divorced, without children. Now he had to fly back to California, inform his wife and stepson he was indeed going to the Middle East war zone, and perform all the mundane tasks like ensuring his Last Will and Testament were up-to-date. In the end, Brian spent five weeks in the Middle East, first covering the daily briefings in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and then Kuwait, after it was liberated. The only real danger he felt was in Saudi Arabia. For those old enough to remember the Gulf War you’ll likely remember the daily news reports of Iraq launching Scud missiles at both Saudi Arabia and Israel. Well, the daily briefings Brian covered were at the press’s hotel across the street from the Saudi Ministry of Defence, a prime target. The notoriously inaccurate Scud missiles never landed anywhere near him and he went back home safe and sound.

Back home in Los Angeles, Brian covered what may have been the biggest story of his journalistic career — certainly the most famous, or to perhaps use a better word: infamous. Starting with jury selection in late 1994 and the opening statements on January 24, 1995, Brian covered every single day of the O.J. Simpson trial. When I asked him about his thoughts of the trial, looking back, he said that “it’s hard to sum up in a few words”. Because of the immensity of news coverage, the electronic press were set up in a separate room where they watched the trial on live feed from a master camera and they could file their stories as necessary. That is one of the memories that stands out for Brian — the sheer work of paying attention to every moment in the courtroom, while dubbing key sound bites for network audio packages, plus doing several live shots each hour, including in the top and bottom of the hour newscasts. I can hear him in my head: “This is Brian Bland reporting live from the O.J. Simpson Trial.”

In terms of particular moments, Brian remembers what is now widely understood as one of the prosecution’s greatest bungles — co-prosecutor Christopher Darden asking O.J. to try on the glove. All Brian could think of at the time was, “are you kidding me, O.J. is a professional actor, there’s no way that glove is going to fit.” The other memory Brian shared was one that is similar to many who watched the trial from their homes: the faces of Ron Goldman’s father and sister when the not guilty verdict was read out loud.

Obviously a broadcast journalism career that spans 1968 to 2006 has many memorable moments but the last one I will convey is a story that became quite personal for Brian. The 2000 Democratic National Convention was held at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, from August 14 to August 17, and along with the delegates came the protestors. One group of demonstrators went mobile with a giant bicycle rally to protest air pollution. Associated Press dutifully purchased a brand new bike for their 59 year old intrepid broadcast correspondent and off Brian went, recording gear strapped to his chest, cycling behind the protestors who did nothing more than shout slogans at gawking citizens. When the protest ended, Brian followed a group of about a dozen cyclists who were heading back to the Staples Center when, all of a sudden, a swarm of motorcycle cops blocked their path, forcing everyone off their bikes, including Brian. Not a single cop, including the commanding officer who Brian knew, had any regard for his press credentials. After several hours he found himself in lockup for another six hours before he and a reporter from the Chicago Tribune were released. The bicyclists, though, were held for three days and Brian became part of their class-action lawsuit for false arrest, which delivered him a “tidy sum”. I didn’t ask Brian how many zeroes there are in “tidy” but he did tell me that he and Jeanne used a portion of the money six years later to throw him his own rather elaborate retirement party. I have to say, a journalist using money from a lawsuit to celebrate his 38 year career sounds like a great “eff-u” to the Los Angeles Police Department.

Before my wife and I fled back to Canada with the rapid spread of Covid, I had one particularly fine Tuesday afternoon listening to Brian read his latest essay. If you read my Profile on the entire group, Write Away, you will know that one of the writing exercises is to take an agreed upon list of five disparate words from the previous week and create something — fiction, non-fiction, poetry — the form does not matter. Sometimes we have everyday words and sometimes people will toss out one that’s little used like revanchism. Go ahead and look it up — I had to. That Tuesday, he delivered a 900 word essay that began by describing the Albert Bettannier 1887 painting La Tache Noire which depicts, in Brian’s words, “young cadets being taught revanchism, literally the longing for revenge, in this case, getting back the land that France used to own.” From there he told us: “It’s fitting that the French word for revenge lent its meaning to the desire of getting land back. Fitting, because the word is often used in connection with events before and during the Second World War, when Germany again grabbed Alsace-Lorraine from France and took over the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia, thereby returning hundreds of thousands of German speakers to the Fatherland.

“The greatest conflict in human history ended in 1945, and 51 countries founded the United Nations in October of that year. Despite that, some leaders in the twilight of colonialism were still incapable of realizing that Belgium could not really own the Congo, France could not truly own Vietnam, Britain could not own Rhodesia, the U.S. could not continue to own the Philippines.”

Brian continued to explore that single word, revanchism, through the 20th Century and into 2020, noting Russia’s territorial claims in Crimea. While the rest of us — well, at least me — struggled to understand how to use that word in a sentence, Brian provided us an erudite geo-political history lesson. Yes, for me his professional broadcast voice delivers, but the package is intellect bound with terrific formidable writing skills. I get to enjoy those skills when Brian emails me something he has written but I sure hope, if not 2021 at least in 2022, I can get back around that winter’s table of writers on Tuesdays and hear him read those words aloud.

I finish this series on Write Away with a profile of Saul Isler. To encapsulate Saul in a sentence or two is impossible so you’ll have to wait and read about this intriguing fellow in the next instalment.

I hope you come back.

4 Comments

Add comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

A wonderful read, Ed. I am really enjoying reading about your Write Away friends. Brian sounds like an amazing journalist who has lead a most interesting life, with amazing stories to tell.

Yes, a great group of folks.

I wonder how Brian feels about Putin and revanchist behavior at it’s best.

The first email I received from Brian after the invasion was on that very word.