During the summer of 2019, nearly forty years after I last saw Mark Mercer, we sat in The Richmond Tavern, a beer joint in the centre of our hometown, London, Ontario. The Richmond Tavern is one of the few remaining old time bars in London; long gone are The Rideout, The Oxbox, The Embassy, and Montcalm Secondary School’s favourite haunt, The Barn. Earlier in the year I’d reached out to Mark through Facebook. We emailed back and forth, me trying to establish the last time we saw one another and Mark suggesting it was my wedding, June 1981. Except, I said, you weren’t at my wedding. To which he replied that he remembered Barb and I were married outside, it rained, and Greg Maslak was my best man. Yes, that was my wedding. I set aside my embarrassment at not remembering one of my invited guests and moved on, which is easy to do with Mark. He doesn’t traffic in such personal peccadillos, neither looking for nor expecting apologies for these trifles.

I first met Mark sometime in the late sixties, when I switched schools, leaving Lorne Avenue Elementary and going to Sir John A. Macdonald in grade six. My father’s plan to return to St. John’s, Newfoundland, had failed and for a bit of time we were living in a fifteen foot aluminum trailer, our home on English Street previously sold, equity squandered, and we waited for subsidized housing — the brand new Ontario Housing Projects at the end of Boullee Street — to be ready. By the time I arrived at Macdonald, Mark lived not far behind the school on Cecilia Avenue, though he had lived for awhile on the other side of Boullee, a small street named Linwood. Born Mark Merchant, he was the oldest of three children, with two sisters Anne and Kelly. Their parents separated when Mark was four and whatever had happened in their parent’s marriage it ended with his mother falling in love with a man named Wayne Mercer, someone she met through Wayne’s brother, a neighbour. Wayne also had a son, Randy, the same age as Mark, their birth dates two weeks apart. When his mother married Wayne, all her children changed their surname to Mercer and Randy became a brother, although he left to live with his mother when he was twelve. Mark stays in touch with his entire family, visiting London from time to time. Randy operates Wayne’s Lanes — as it was referred to years ago — the Fairmont Lanes five pin bowling alley which has been in the family for almost fifty years.

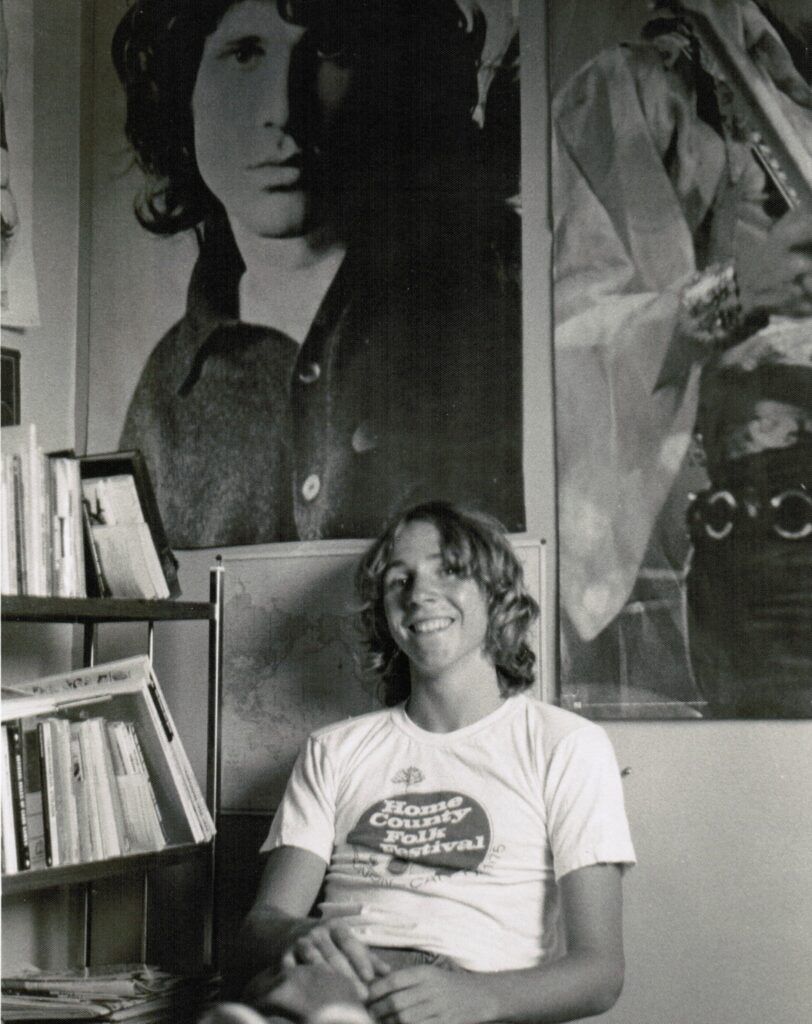

Mark and I didn’t hang out much in elementary school, though I do remember him as the lead in our school’s production of the musical, You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown. That and the fact he had a passion for basketball, making up for his lack of height with great energy on the court as a guard. He continued to play competitive basketball throughout high school and I got to know him much better, exchanging books, sharing a few classes — and more than a few joints — becoming good friends. Along with other friends, we became writer-editors of the school newspaper, The Cougar Times. Mark wrote music columns. I recall his writing as excellent and his rock band reviews quite sophisticated. When Cameron Crowe released his movie, Almost Famous, twenty years ago, a fictional re-telling of the time he went on tour with a rock band for the Rolling Stone Magazine while still in high school, I immediately thought of my old friend Mark Mercer. Given different circumstances, I could imagine Mark’s high school writing convincing the pop culture magazine he was much older, and they sending him off at fifteen years old, while along the journey he reaches out to the icon of their competitor, Lester Bangs.

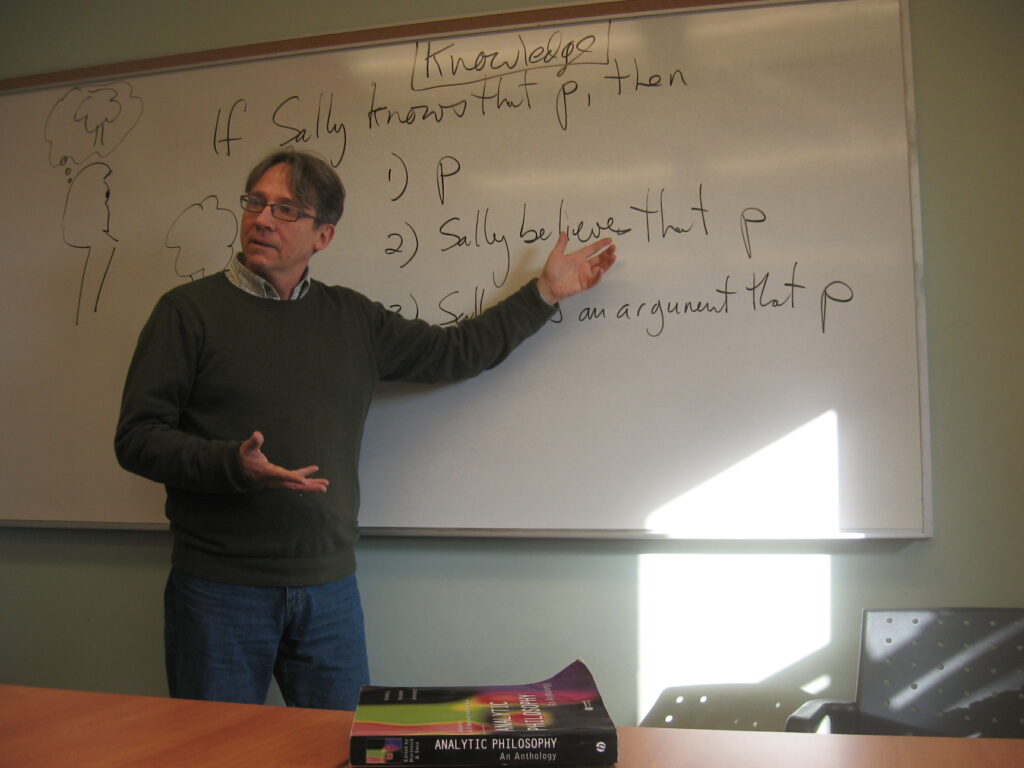

Mark’s life journey, though, took him in a different direction, one that eventually landed him as a Professor of Philosophy at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, serving as the Chair of Philosophy for eight years. That path began a year after graduating from Montcalm in 1976, by attending Carleton University in Ottawa. He did go to the University of Western Ontario right after high school, but to work in the campus bakery in order to earn some money. His plan to study English Literature changed when he arrived at Carleton and was intrigued by the fact they had a film studies department. One drawback: the department was still in development and didn’t, initially, have enough courses to grant a Honours Bachelor of Arts (four years of study as opposed to a three year Bachelor of Arts). Mark took advantage after third year by going back to London, working a variety of menial jobs to again earn some money, and returned twelve months later to finish. Two important changes occurred. First, inspired by a philosophy course he had taken in third year, he spent his time, when not working, reading various philosophical works. The second change came upon returning to a film studies department dominated by “postmodern deconstruction theories”. While Mark may not have established himself in a particular philosophical tradition at the time, he was on his way, wanting clarity in arguments, firm logic, empirical understanding and rejecting concepts that, in his view, embrace the jargon-laden language of phenomenology, structuralism, and post-structuralism.

He turned to the philosophy department, staying at Carleton, and while in the qualifying year for his Masters met Kate Talmage, at the time a second year philosophy student. Mark refers to her as a “brilliant philosopher” whose father, Stephen, was a professor in the department. Apparently, “some of the students thought we were a match and conspired to bring us together.” It worked, at least for a decade, as they pursued their PhD’s together at the University of Toronto and then, after each being granted postdoctoral research fellowships, travelled to University of California, Berkeley. By then, Mark, as with Kate, had come to firmly align with the Western philosophical tradition referred to as analytic, in contrast to what is known as the continental tradition.

As Mark explains: “By the beginning of the twentieth century, the division between empiricists and rationalists had morphed into what is now called analytic (or Anglo-American) philosophy and continental philosophy (it was mainly Germans and the French who philosophized in that tradition). Friedrich Hegel, Søren Kierkegaard and Edmund Husserl are foundational continental philosophers, while analytic philosophers take their inspiration from Gottlob Frege, Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein. A hint of the empiricist, rationalist division continues to mark the two traditions. More importantly, we analytic philosophers are put off by the obscurity of continental writing and the self-dramatizing pose many continental philosophers affect. I suppose the continentals say mean things about the analytics, but the way they write, who’d know?”

At Berkley, there were a couple of well known American philosophers, John Searle and Donald Davidson. (For more, follow this link for John Searle and this link for Donald Davidson.) Mark says, “Kate and I were already working in the analytic style or tradition. I had some exposure to continental philosophy at Carleton and then at the University of Toronto but I was never at home there. Too woolly for me. At Berkeley, we spoke philosophy regularly with Donald Davidson. We had at least a couple meetings with Searle. We palled around with some of the doctoral students, being closer in age to them than to the professors.” They lived in Oakland at the time, near Berkeley, but left after one year when Kate was offered a tenure-track position at the University of British Columbia. From what Mark told me, though, the year at UC Berkeley surrounded them with extensive drama, “being the year of the Oakland hill fires, the return of capital punishment to California, the Rodney King riots, the eviction of the squatters from People’s Park, and a big free concert of Bay Area musicians following Bill Graham’s death.” If you don’t know Bill Graham, he was, among many things, a significant rock concert promoter who died in a helicopter crash. The gathering of musicians who honoured him in Golden Gate Park, with 300,000 fans in attendance, included Santana, the Grateful Dead, John Fogerty, the reuniting of Journey, and of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

Mark transferred his post doc from Berkeley to Burnaby’s Simon Fraser but by the time they settled into faculty housing on the UBC campus, where Kate began teaching, they had drifted apart and split up at the beginning of summer. Mark stayed in BC, moving to Kelowna to teach at Okanagan University College (now UBC Okanagan) on an eight-month contract during 1993-94. In the Spring of 1994, he interviewed for a one year position at Brandon University in Manitoba, getting much more than just the job, meeting his future wife, Sophie Beaulé.

“At the beginning of September, 1994, I arrived at the Winnipeg airport. I had a map open trying to figure out how to get to the Winnipeg bus station to get a bus to Brandon. A woman with a thick Quebec accent asked if I was the new philosophy professor at Brandon. It was Sophie. She had been hired three years earlier at Brandon as a professor of French. She had been at the presentation I had given as part of the interview process at Brandon U (I believe I gave a talk on the appreciation and evaluation of art in the absence of objective or set standards). She told me I could come with her and catch the bus to Brandon right from the airport. The bus was full and we didn’t get to sit together. Our offices at Brandon were one floor apart. I asked her out, we had a good time, and I moved into her townhouse on 27 September, almost four weeks after we met.”

While the idea of tenure sounds very appealing to those of us outside of academia, the process of obtaining a tenure-track position at a university in your field of study is not easy, to say the least. For Mark and Sophie, the prospect of both securing tenured positions at the same institution or, at least, in the same community, looked unlikely. The fact they are both tenured professors, now, at Saint Mary’s (Sophie in Modern Language and Classics) is quite fortunate. Of course, it took time.

“I taught at the University of Calgary from 95 to 97,” Mark said, “but came back to Brandon as often as I could. For 97-98, I applied only for tenure-track positions, rather than contractually limited or sessional positions, and failed to get one. So I stayed with Sophie for 97-98 and wrote papers. It was like a sabbatical except that I had no income. We got married in July 98. I had been getting more interviews in the States than in Canada and we thought that being married might make things easier if I were to get a job in the States.” Applying for a job at St. Cloud State in Minnesota brought Mark an interesting experience: he applied for the job but received a rejection letter, then, a couple of months later they called him on the phone and offered him the position without an interview.

Though he was short listed for a tenure-track position at St. Cloud, Mark continued reaching out to other universities, finally finding success. “In the summer of 1999, I was offered tenure-track positions at both Okanagan and Saint Mary’s. I chose Saint Mary’s because opportunities for Sophie looked better in Halifax than in Kelowna, if we decided that Sophie would join me rather than me return to Brandon. Sophie was on pregnancy/parental leave for 1999-2000. During that year, a position was advertised in French at Saint Mary’s, she applied, and in 2000-2001 began her Saint Mary’s years. We each gained tenure on time and have been twice promoted; we’re both full professors.”

About that pregnancy/parental leave — their first son, Étienne, was born in November 1999 and their second, Guillaume, in December 2001.

While Mark continues to read, develop and write about philosophy, whether delving further into the pre-Socratic philosophers of ancient Greece, or writing text books on introduction to philosophy, and critical thinking, and his teaching focus, ethics, it is the issue of intellectual autonomy at universities that has consumed much of his time in the last fifteen years. He reveals, in his published essay, “Why Study Philosophy”, the heart of the matter. “At its best, the university experience is one of overcoming ignorance and reliance on traditional or customary beliefs. Not only does an educated person know things, he or she is able and dedicated to thinking for herself. To come to think for oneself, one has to bring one’s deepest beliefs to consciousness and lay them open to criticism and reform.” To Mark, the swelling dogmatic opposition to free inquiry, especially when that inquiry raises high emotions among many people, has led to cancel culture becoming the norm at Canadian universities. In stark contrast, and leadership, to the stifling of inquiry, argument and debate, Mark joined the Society for Academic Freedom and Scholarship (SAFS) in 2006 and became president in 2015.

One of Mark’s closet friends is the Canadian philosopher Andrew Irvine who has published extensively, particularly on Bertrand Russell, and written the play, The Trial of Socrates, which has been staged in Canada, USA and Europe. Though they met off and on over the years it was when Mark joined SAFS, where Andrew was already on the Board of Directors, that they became close friends. They are simpatico regarding civil liberties and free speech, particularly as it relates to university campus, and Andrew has edited a collection of Mark’s essays on the subject that they are currently looking to publish.

In the introduction to this book, In Praise of Dangerous Universities and Other Essays, Andrew writes that Mark “is, quite simply, a national treasure. A tireless defender of liberal learning and academic freedom”. As Andrew further explains, Mark sees that “the purpose of university instruction is not just to make students more knowledgeable. Instead, it is the job of university instructors to model the kind of intellectual autonomy that defines a liberal education. Teaching, on this view, is aimed at helping students become researchers in their own right. It is aimed, not at advancing some particular set of beliefs but at helping students to inquire, interpret and appreciate the world in which they find themselves. It is the job of a university education to help students to learn to think for themselves. This view of liberal learning is strongly connected to academic freedom.”

The title of Mark’s book is taken from the lead essay where Mark lays the groundwork on the first page. “A safe university isn’t a university free of theft, vandalism and violence. It’s not one where the ice is cleared quickly from the sidewalks. Rather, a safe university is a university at which no one will hear racist, sexist or homophobic comments. It is a university where no one will hear discriminatory slights against a person’s religion, nationality, age or disability, or any other unwelcome comments.” Opposite to that, “A dangerous university is not one given to making people feel good about themselves, at least not on principle. It is not about affirming identities or celebrating cultures or contributions. Rather, a dangerous university is about investigation and criticism, about constructing from evidence and argument alone a view of the world, and about knowing how to put that view to the test. It is a university at which one will encounter disturbing ideas and values, sometimes spoken by the very people who advocate them. It is a university at which people speak freely and at which no view is out of bounds as a topic of discussion.”

Mark Mercer’s blunt appraisal of what free speech actually means creates emotional discord for many, if not most, in our contemporary society. That emotion also creates the false impression to these people that, while Mark demands the right of speech for people with disturbing ideas and values, he somehow aligns with these ideas or values. Nothing could be further from the truth. In doing a quick word count of his book I found the word “respect” stated sixty-four times and he places multiculturalism in the centre of his view of a good society. “Multiculturalism, democracy and liberalism: these are essential to how we live”. But if we are going to get to the essence of things, that essence is only possible with critical thinking, dispassionate inquiry.

In his essay, “Taking Offence”, Mark writes “a university helps students to see what it’s like to be passionately dispassionate about argument and inquiry, and then leaves it to them. The joys and rewards of being a critical thinker are many and compelling. For that reason, it’s unlikely that people schooled in critical thinking would choose not to think critically. That public discourse in our country and even in our universities is marked by displays of offence, charges of arrogance or hypocrisy, and demands for apologies, rather than by critical investigation and discussion, is strong evidence of our failure as professors. One of the joys of being a critical thinker is that one is never offended. That’s not to say that critical thinkers are never upset or hurt by the course of events or by what they hear. But because their attention is on the claims themselves and the arguments for and against them, the question whether the claims are offensive is of little or no interest. Since they don’t care, they can’t be offended. This gives thinkers a tremendous freedom to evaluate arguments on their own merits. That someone compares abortion to the Holocaust, for instance, is a matter of indifference to critical thinkers. Critical thinkers are interested only to evaluate that person’s arguments against abortion. On the other hand, an almost sure sign that a person isn’t thinking critically is his inclination to exclaim ‘That’s offensive!’”

To understand further Mark’s thoughts on the absolute need for dispassionate inquiry, I’ll leave the reader to ponder his exploration of all these things for themselves by reading his writings on his web site, professormarkmercer.ca or on SAFS’s www.safs.ca.

On the day-to-day side of life, Mark is now on sabbatical with Sophie in Montreal, although not the experience they were planning. As we all say of our plans these days: damn Covid! The pandemic also disrupted plans for the government of France to name Sophie as a Chevalier (Knight) in the Ordre des Palmes académiques on 1 January 2020. Mark says that she’ll receive the honour at a dinner in the fall of 2021, if all goes well. According to Wikipedia, the honour is a “national order bestowed by the French Republic on distinguished academics and teachers and for valuable service to universities, education and science.” To give you an idea of how serious this honour is, you have to have permission from Canada to accept it — given that it is bestowed by a foreign nation — and there are rules to how you display the “palm”. As Mark told me, “Sophie received a letter from the Governor General of Canada, granting her permission to accept this award and reminding her that she must wear the palm below any honours she’s received from Canada.”

Not small stuff, that.

Both of them will return to teaching at Saint Mary’s in the fall, and their boys are off to university. When I wrote an email asking Mark about what the future holds (to the degree any of our plans hold true these days), he replied: “We both enjoy teaching so we don’t have plans to retire right at 65 or 66. On the other hand, it’d be great to have time for writing and other pursuits before we get too old to be any good at them. Likely, then, we’ll teach for another six years, have one last sabbatical and then retire. So 2028-2029 might be our last year.”

Regarding his activism fighting for civil liberties and freedom of speech? “I intend to step down from the presidency of the SAFS in May 2023. That will be at the end of eight years as president. I’ll step off the SAFS board in 2025 so that new people can be elected. I’d rather be writing, reading and teaching than working with an activist organization (though disgruntled academics can’t really be described as activists, which might explain why we’re losing so badly). I’m an accidental activist. I think it can’t hurt to lend a hand and then somehow someone manages to get me put in charge.”

Who knows what Mark Mercer will find himself in charge of in the future. For me, I just hope the waning of Covid allows him to be in charge of his own plans to visit London this summer so I can take the 90 minute drive from Georgetown down the highway to our hometown and catch up over another beer. The other hope is that The Richmond Tavern survives the plague.

Next up is Gavin Barrett who, from Bombay (now Mumbai) to Hong Kong to Toronto, has lived a life of creativity, of communication. His first poetry collection, Understan, was published last year and to give you a sense of this intriguing writer’s story, born of Anglo-Indian and Goan East African parents, I quote from his own website: “His commercial writing has been published in 35 countries, helped elect prime ministers, drew the ire of the lawyers for Dolly the cloned sheep, attracted an angry crowd in Lagos, has been studied in business texts in Canada and India and was critiqued by a fictional character in a John Irving novel.” And that, folks, is just the surface.

I hope you come back.

2 Comments

Add comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

In reading this bio of Mark Mercer, I was reminded of my early Uni days at United College in downtown Wpg, which, at the time affiliated with the U of M, in 1967 became the U of Wpg. I was in that last graduating class. Headed for post grad Education 67/68 at U of M, I began my studies the fall of ‘64 with a major in French and double minors of English & Psychology. However, some time into my 1st year, I discovered I was required to take one Philosophy course. I quickly signed up for Moral Political & Social Ethics, the only course which fit into my 2nd year time table. It was taught by Dr Shimizu who literally had to be the most boring Prof I had in 4 years of study. I vaguely recall having a double class of two 70 minute segments with a 30 minute ‘smoke’ break in between.

I learned to smoke in gr 12 while attending the collegiate part of the college in 63/64. I must add I paid for that year as well as 4 years of Uni with babysitting & working part time at Eaton’s to make enough money for tuition & books while living at home.

Back to Dr S’s boring lectures!! It became a toss up whether I’d show up for the 2nd half after the break or leave as soon as the break started. This was not the dedicated student I had been in high school to skip classes but…. At any rate, I passed with a 51%!!! It later turned out Philosophy was dropped as a requirement for Education!!! WTF!!!

I realize I just wasn’t ready for Philosophy. Growing up, as the eldest of 10, with very strict parents who never seemed to have time to discuss anything of any depth with us kids, I never learned to analyze or do any critical thinking. In fact, we were lead to believe children should be seen & not heard. In school, unless I absolutely loved the course, I rarely contributed.

In retrospect, if I could go back, knowing what I know now, I’d likely find philosophy far more stimulating, understanding that participation be a significant key to stimulation & enjoyment.

Thanks for the read, Eddie!!

PS I quit smoking in 1982.

Thanks for the story — and glad you quit smoking!